Romeo is a Dead Man is a restless game. Within the first hour, there’s: an establishing shot of a diorama village, its buildings and streets rendered in what looks like felt and Styrofoam; a scene presented as if captured by a police camera, with scanlines overlaying a few minutes of video that wouldn’t be out of place in a found footage horror movie; and an animated sequence rendered in scratchy, expressionist linework that gives way to a slow zoom over comic book page panels, the dialogue in cartoon bubbles read out through voiceover.

All of this creates a pretty disorienting first impression, an overwhelming entry point to a game with a vibrant spirit that attempts to maintain a high level of energy throughout its runtime. It’s also an appropriate way to establish the high-concept trappings of Romeo is a Dead Man, and of the fractured sci-fi landscape its protagonist suddenly finds himself transported into following the game’s frenetic opening.

In short, the premise goes like this: Romeo Stargazer is a small-town deputy cop who is brutally maimed by a zombie-like creature on a night patrol. He soon finds himself resurrected from death, head encased in a chunk of plastic that resembles a high-tech motorcycle helmet, and inducted into the memorably named FBI Space-Time Police. He’s dubbed ‘DeadMan’ by his new colleagues, for obvious enough reasons, and joins with them to travel time and space to thwart multidimensional villains and attempt to find his lost girlfriend, Juliet.

Time and space have broken apart in Romeo is a Dead Man, the nature of reality collapsing around the same time that Romeo was saved from death and whisked away to the Space-Time Police. This not only serves as a good excuse for creator Grasshopper Manufacture to flit between visual styles throughout the game, but also as a way to set its action against constantly changing backdrops.

A different sort of time cop

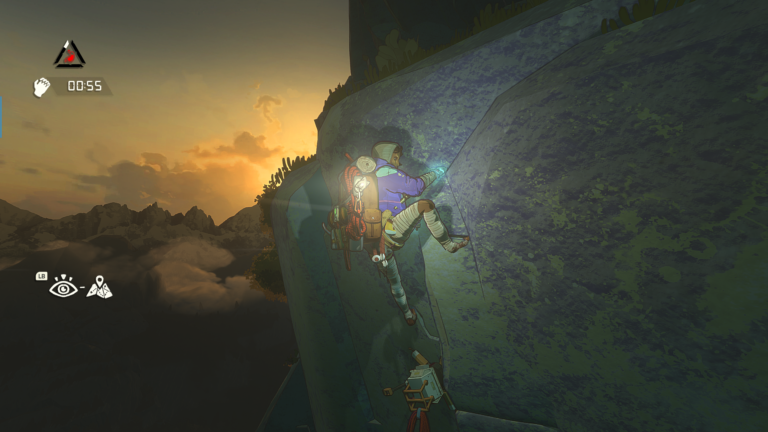

The bulk of Romeo is a Dead Man sees the protagonist sent to different decades in the history of his hometown of Deadford, each one basically a discrete level that ends with him confronting one of the interdimensional criminals wanted by the Space-Time Police. He explores locations like a shopping mall just about to open in 1983, an asylum in 1992, and Deadford’s city hall in two different decades. Within each of these spaces, he also finds floating television sets that zap him into an underlying ‘subspace,’ which consists of grids of blaring neon stairs and hallways corresponding roughly to the real world’s architecture.

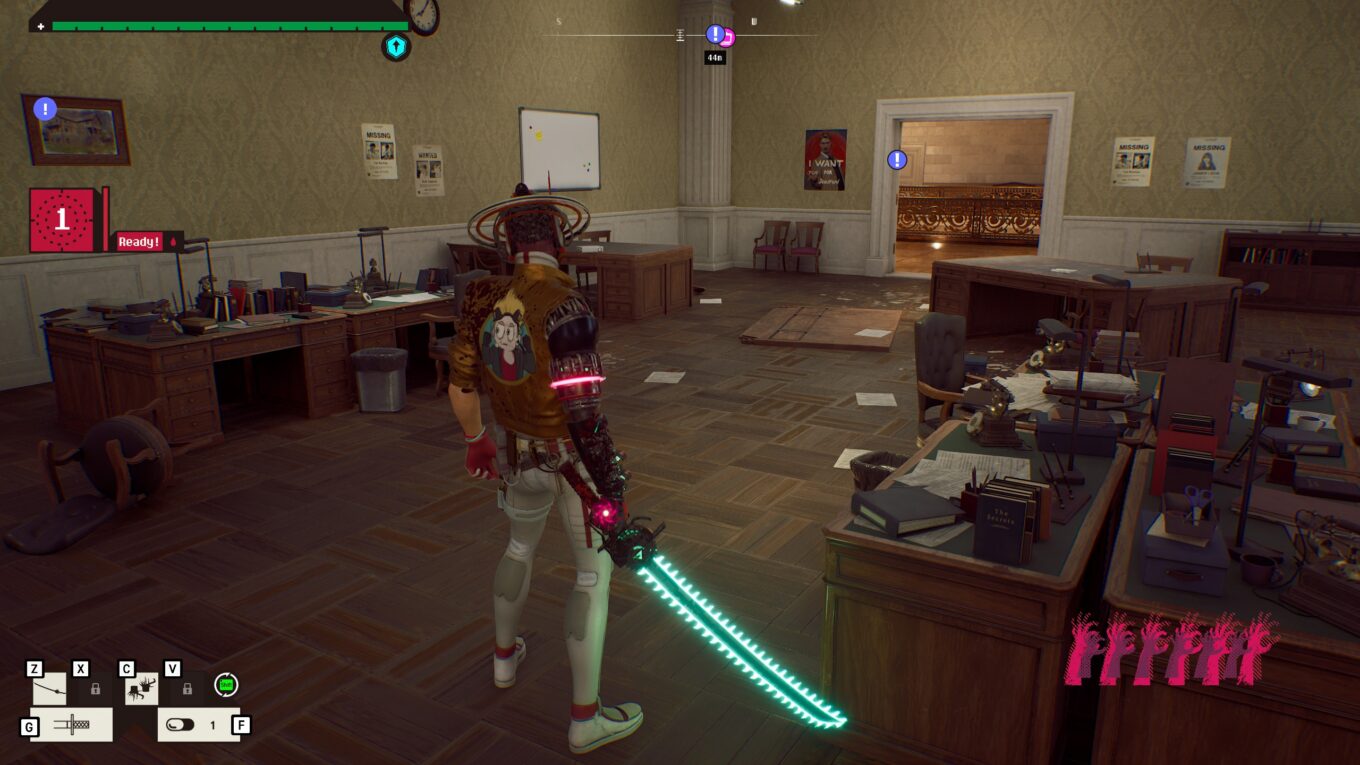

Most of what Romeo actually does while locating his target is slash and shoot through waves of more-or-less humanoid monsters called Rotters, many of whom resemble shambling zombies. Romeo has an arsenal of four different melee and ranged weapons, unlocked over time and ranging from a sword and pistol to a shotgun, spear, rocket launcher, and more. The fights are serviceable, but increasingly numbing as time goes on, the result of Romeo’s limited move set and the choreography of enemy encounters that typically involve a selection of creatures swarming into an area with mindless ferocity.

Romeo has a faster, weaker attack and a stronger, slower one, with a handful of dashes and dodges unlocked at occasional intervals throughout the game. The player can switch between shooting the equipped gun and swinging a melee weapon as needed, trying to blast away at glowing weak points to more efficiently take down enemies or simply slashing at them until they collapse into a pile of dead goop.

There’s a great sense of weight to these melee attacks, especially the crunching grind of unleashing the ‘Bloody Summer’ special that’s powered up by absorbing the lifeforce of dead enemies, and the visual spectacle of a screen filled with geysers of gore enlivens each encounter. The combat is just too limited by Romeo’s humble selection of abilities and the enemy’s behaviour to sustain the sheer volume of it that fills each location. And Romeo is just sluggish enough that stumbling into an enemy attack often feels less like the result of a player’s missteps than an unresponsive main character.

Replacing menus with mini-games

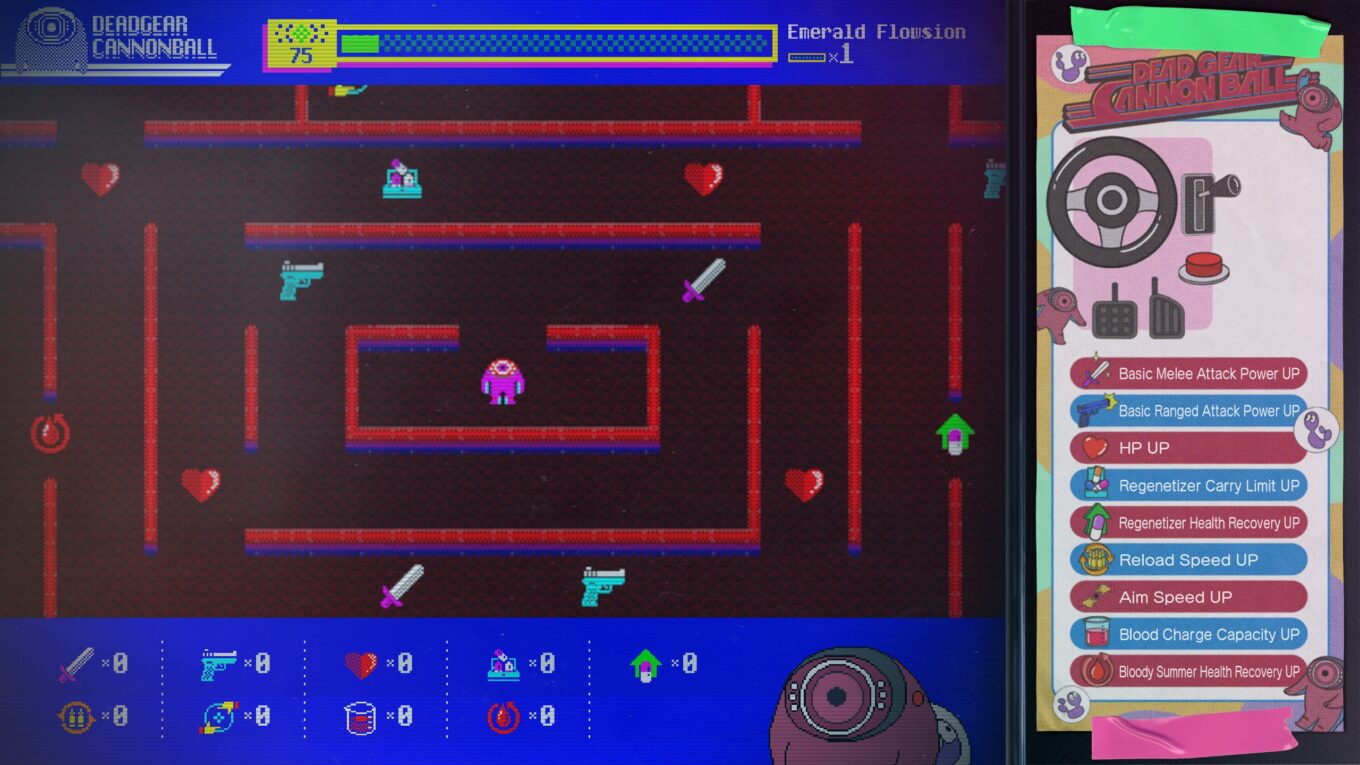

The core design of the fights gains extra colour from an accompanying range of upgrade materials and systems as overwhelmingly varied as the opening hour’s aesthetic flipbook. While fighting through levels, Romeo collects green and red items used to strengthen weapons. He also gains another currency by defeating enemies that’s spent on boosting his own stats through a retro in-universe videogame that involves navigating a little astronaut character through a Pac-Man-style maze littered with items. Back at the spaceship homebase, rendered in throwback sprite work that resembles an overhead Super Nintendo role-playing game, where he can visit his mom and drop off cooking ingredients to have her prepare different curries in a timing-based mini-game, each of which empowers him in combat when eaten.

The most involved of these many systems sees Romeo head to his sister’s quarters on the ship to cultivate garden plots that yield extra combat abilities, personified as monsters called Bastards. Though these work in battle as a wide array of special skills, one launches damaging lasers, one creates a healing area, another freezes enemies in place, they’re presented through a much more involved bit of design than their utility would suggest. Each Bastard starts off as a seed, has to be planted in a patch of soil, and requires waiting for enough real-world time to pass before they can be harvested and assigned as Romeo’s skills. They pop out of the ground as moaning ghouls and are assigned titles from a roulette of randomized descriptors and names, like ‘Stingy Bianca’ or ‘Sweats Year-Round Orson.’ They can also be fused together to create new, stronger versions, as well, and this takes the form of automated fights where one Bastard subsumes the other. It is, like so many of Romeo is a Dead Man’s systems, a convoluted, but aesthetically compelling way to present a straightforward concept.

Lost in sub-space

It’s important that these complications exist because the design they surround isn’t nearly as exciting. As with the combat, the level design becomes rote before long. The environments are labyrinthine and too drab to distinguish one hall or hub area from another, leading to a lot of accidental backtracking and frustration figuring out how to get to one point from another. Worse are the subspace sections necessary to reveal new areas or unlock doors in the real-world. With only gridworks of abstracted space to use as reference points, it’s far too easy to get lost going back and forth on the way to an objective. Unexpected changes in form and tone occasionally appear, like an extended homage to survival horror games that require simple stealth and puzzle-solving while Romeo’s weapons are inaccessible within the confines of an abandoned asylum. But instances like these are too few and far between to keep the game as lively as it is during its best moments.

The drab environments and fights end up feeling, at times, like paying a price for the reward of getting to the new plot points or swerves into unexpected formal experiments that make up Romeo is a Dead Man’s narrative. That narrative starts off strong, with the nature of the world and relationship between characters just opaque enough to create intrigue. After a post-introduction lull, the story begins to cohere about halfway through the game, detailing Romeo’s pre-DeadMan life and revealing, through snatches of dialogue, the plot’s intentions.

She speaks, yet she says nothing

The game’s themes of predestination and longing are striking once they fully develop toward the game’s finale. At the plot’s most powerful moments, they are explored with a palpable fury, most noticeably in the gory dispatch of the first ‘space fugitive,’ whose origin story involves the massacre of slaves during the American Civil War and terminates with him gloating over his time-hopping evil as Romeo prepares to kill him in the 1980s. Here, and in other tragic post-boss fight scenes, the point of a story about universal villainy and systemic harm clarifies to proper dramatic effect.

Otherwise, there’s too much of an ironic distance kept from creator and character to feel a sense of real investment in the ideas encountered throughout the game. Romeo is a Dead Man’s meditations on the aimless feeling of a life on autopilot are captured well by playing through level after level of a good enough videogame that never seems like it’s in any hurry to arrive at any plot point in particular. But it doesn’t connect with the heart as much as the brain.

The lack of real human feeling is compounded, too, by the game’s relative disinterest in the women among its cast, who are defined more by narrowly defined roles than real personalities. While characters like Romeo, his grandfather, and other male crew members and villains, have backstories and motivations that vary enormously, the game’s women are slated into the roles of mother and sister, therapist and scold, and, in Juliet, a sort of monolithic icon of universal romantic love that can never be properly attained. The character writing is flat in general, but, in these cases, it’s basically one dimensional.

All of these issues interfere with what successes the game does achieve. As much joy as Romeo is a Dead Man may find in flitting between stylistic ideas, in a formal and visual sense, it never comes down to earth long enough to truly connect. There’s a lot to admire in its approach to the action game, but the creativity of its varied concepts is let down in the execution.